As required by the Federal Aviation Reauthorization Act of 1996, the Commission has analyzed the FAA's budgetary requirements through FY 2002 and assumes the agency's own budget predictions to be reasonable in a status quo environment. However, the Commission also believes that the status quo cannot be maintained and that total system costs can only be completely determined when the FAA establishes a credible cost accounting system. Moreover, the Commission recommends management efficiencies and productivity enhancements aimed at reducing the FAA's operating costs, but recognizes the FAA's need for increased capital investments. Below are the Findings of the Commission regarding the FAA's future requirements, including a discussion of cost saving opportunities.

The validity of the FAA's future financial requirements have been debated vigorously in the aviation community over the past few years. Despite staffing reductions, the FAA's operating costs have continued to increase. Outside critics argue that the FAA should be able to reduce cost through management efficiencies and productivity enhancements. The FAA responds that workload is increasing as the aviation industry continues to grow and new services are provided. Additionally, the FAA has stated that transitioning to modern air traffic control equipment often requires maintaining dual FAA systems until all aircraft have corresponding avionics upgrades.

In June 1995 the FAA projected its financial requirements to be $12 billion above allocated budget targets for the period from FY 1997 to FY 2002. The Congress and the aviation industry questioned the FAA's estimates resulting in the Federal Aviation Reauthorization Act of 1996 requiring an independent financial assessment of the FAA's budget requirements from FY 1997 to FY 2002. Coopers & Lybrand conducted the independent financial assessment and determined that the FAA's calculation of requirements was reasonable within a status quo environment.

Coopers & Lybrand argued that this status quo was unsustainable and suggested a number of cost-saving opportunities. (They also recognized the difficulty of achieving agreement on reductions because of industry or congressional opposition.) Most cost saving recommendations are associated with the FAA's increasing operating costs. In terms of capital investments, Coopers & Lybrand pointed out potential cost increases the FAA may face, such as:

As stated above, the Commission agrees with Coopers & Lybrand's findings regarding both the general validity of FAA's future requirements and the unacceptability of a status quo environment. The Commission's recommendation for a Performance Based Organization discussed in Section IV should provide a catalyst for cost savings. The Commission strongly urges the FAA to look at improving cost management through a new cost accounting system designed to identify "best practices" and efficiently allocate resources. Additional recommendations for cost savings are discussed at the end of this Section.

The Commission recognizes that under the proposed structure where the FAA is able to borrow and function like a capital intensive business, annual financial requirements may change significantly. Any additional funds made available from financing capital investments or operational cost efficiencies, may be needed to fund new capital requirements in both the FAA's air traffic control facilities and equipment modernization program, and the airport grant program. The commission recognizes, however, that funds are scarce with many competing demands, and providers of capital will resist additional funding for the national airspace system unless they are confident the funds will be invested effectively.

Most capital investments in air traffic control (ATC) modernization do not generate immediate reductions in operations and maintenance costs. In addition, for many equipment modernization programs, existing systems must be phased out to minimize the impact on aviation users. In some cases, this means overall operating costs can increase since two systems may provide the same function during the phase-out process. The transition from a ground-based to a space-based navigation system is an excellent example of where the FAA will be required to maintain dual systems until the aviation community is properly equipped. The Commission believes that improved coordination between FAA planning and industry equipage can help minimize these costs.

While some investments will lead to efficiencies and reductions in FAA operations and maintenance costs, other investments will lead to new sites, new functions and new support staff. The integrated terminal weather system (ITWS), for example, will provide controllers more accurate and timely weather information. ITWS will save the airlines significant operating costs by reducing delays. When deployed, however, ITWS will increase the FAA's operating cost. This helps explain the FAA's dilemma in prioritizing programs within budget constraints that are in no way connected to the benefits to the aviation industry. These nuances account for why a decrease in the FAA's operating costs is not seen either during or right after modernization. Most FAA savings for capital investments in the FY 1998 to FY 2002 time period will not be realized until after FY 2002. However, airline operating costs during this time period should be reduced as a result of the FAA's capital investments.

Another factor contributing to the difficulty of cost reductions is the more than 15% decrease in effective buying power of the budget since FY 1992. This decrease has occurred over a period where aviation activity increased by nearly 15%.

The FAA's budget is divided into four accounts: (1) Operations, which supports FAA air traffic controllers, aircraft and airline inspectors, security specialists, and headquarters staff; (2) Facilities and Equipment (F&E), which supports capital equipment expenses such as new radar equipment, air traffic control towers, and air traffic controller equipment; (3) Airport Improvement Program (AIP) grants, which supports capital needs at airports such as new runways and taxiways; and (4) Research, Engineering, and Development (RE&D), which supports various research projects including development of new air traffic control automation tools, improved explosive detection equipment and lighter and stronger material for aircraft manufacturing. The following discussion focuses on the FAA's funding requirements for the Operations, F&E, and RE&D budget accounts followed by a discussion of specific cost saving recommendations. The AIP budget is discussed in a separate section on airport needs.

Much of the FAA's funding erosion has resulted from budget targets set by both the Administration and Congress aimed at reducing the deficit. Through FY 1997, the budget decline has been heavily skewed to the F&E and AIP capital accounts, which have been reduced by 19% and 23%, respectively, since FY 1992. The Operations account actually has grown by about 12% largely in response to increased labor costs (6% per year) and relatively small staffing growth for aviation safety and security (although reductions have occurred in the FAA's administrative staffing). In summary, growth in FAA operating costs and reductions in the FAA's overall funding have resulted in significant decreases in FAA capital investments.

The FAA is at a juncture similar to the one faced 12 years ago by two airports which serve the Washington, DC area. These two airports, which at the time were run by the federal government, had gone for years without significant capital improvement because of federal budget constraints. The capital plant was deteriorating and there was concern that the hundreds of millions of dollars needed would not be made available. Congress decided to create a new organization with budgetary and management options and flexibilities to undertake the development and renewal that was required, and the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority was established. The new terminals and associated work are widely viewed as showcase airport development projects. A similar "breakout" approval is needed for the national air traffic control system.

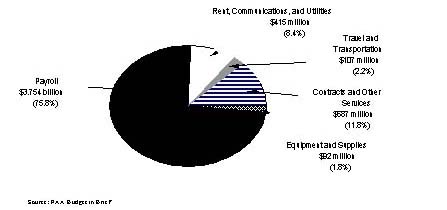

The Operations account finances the personnel and support costs required to operate and maintain the ATC system, and to ensure the safety and security of its operation. It is the FAA's largest account, comprising 58% of the agency's FY 1997 appropriations, and it pays for 17,300 controllers, 8,410 maintenance technicians, 3,247 safety inspectors, 962 security agents, 3,333 flight service personnel, 578 flight inspection personnel, and 12,858 technical and support personnel. Figure 4, below, illustrates the breakdown of expenditures within this category.

Figure 4. Spending Distribution by Major Object Class

within the Operations Appropriation, FY 1997

The Operations portion of the $61.9 billion requirements estimate from FY 1997 to FY 2002 is $36 billion. The Operations requirement estimate provides resources (with inflation) to continue existing services through the six-year period along with the following additional expenses: growth in the controller work force to accommodate anticipated growth in aviation activity, minimal growth in the maintenance technician work force (25 employees per year); and increases of $70 million to $90 million per year for the operation and maintenance of new air traffic control systems going on-line. This Operations estimate also includes growth in safety inspector and security work forces as recommended by the Gore Commission and internal FAA safety studies.

As stated previously, the Commission believes significant, long-term opportunities for cost savings and efficiencies exist within the Operations budget and these are discussed later in this Section. One such positive example has been the contract tower program for Level One towers.

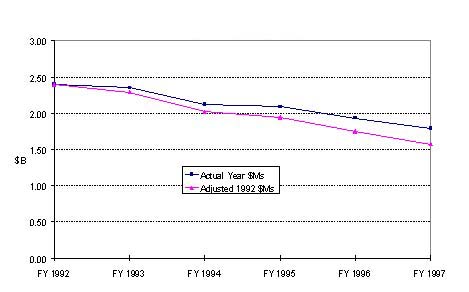

Until 1993, the FAA had premised its F&E capital investment planning on a sustained $2.9 billion annual funding level. In FY 1997, the F&E budget decreased to $1.937 billion which represents a cut of 38% in real annual capital funding compared to FY 1992 actual appropriations and a 45% real cut in F&E funding planning levels since FY 1993. Figure 5, below, illustrates the reduction in F&E funding levels in actual and inflation adjusted values from FY 1992 through FY 1997.

Figure 5.

The FAA capital inventory includes over 24,000 facilities or equipment sites. These include 591 major air traffic control facilities, 396 radars, 1,027 navigational aids, 1,197 landing systems, and 2,427 communication sites. Most of these facilities and systems are being modernized. Many of the FAA's essential ATC systems have been in service well beyond their intended life. Some of the controllers' data displays, for example, have been in operation for more than twice as long as originally expected. Figure 6 illustrates a part of the FAA's aging infrastructure in need of modernization.

| Systems | Average Age (Years) | Quantity | Planned Years for Replacement* |

| ARTS Data Displays | 24 | 100 | 1998-2004 |

| ARTS Radar Displays | 13 | 200 | 1998-2004 |

| Direct Radar Access Channel | 11 | 20 | 2002-2005 |

| Host Computer | 9 | 20 | 2002-2005 |

| Remote Center Air/Ground Communications | 23 | 701 | 2004-2012 |

| Remote Transmitter/Receiver | 18 | 1265 | 2004-2012 |

| Air Traffic Control Beacon interrogator - 4 | 26 | 81 | 1999-2003 |

| Air Traffic Control Beacon interrogator - 5 | 21 | 162 | 1999-2003 |

| Airport Surveillance Radar - 7 | 19 | 35 | 1998-2002 |

| Airport Surveillance Radar - 8 | 16 | 70 | 1999-2002 |

| Air Route Surveillance Radar - 3 | 16 | 22 | 2001-2004 |

Figure 6.

The National Airspace System (NAS) is Aging

NAS Systems Essential for Providing Air Traffic Control Services

* Constrained by Budget Projections

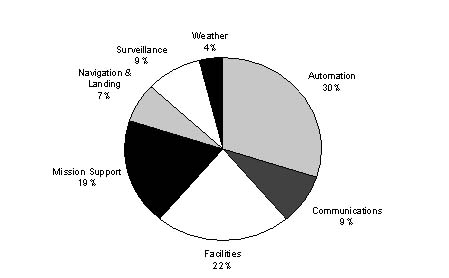

The F&E account contains the FAA's funding for all capital investments (except airport infrastructure), including development, implementation, and the first year's support costs. Currently, the F&E account is made up of nearly 200 separate projects, which are individually justified in the budget request the President submits to the Congress. For planning, purposes, the FAA groups these projects into the following categories: automation, communication, mission support, navigation and landing facilities, weather, and Surveillance.

Figure 7, below, illustrates the percentage of F&E funds allocated to these investment areas.

Figure 7.

FY 1997 to FY 2002 Facilities and Equipment (F&E) Budget Authority by

In the FAA's revised requirements estimate of $61.9 billion, the F&E portion is $13.6 billion. From FY 1999 to FY 2002, the average annual F&E investment would be approximately $2.4 billion (excluding $150 million per year for airport security systems). The $2.4 billion annual level allows the FAA to cost-effectively modernize aging infrastructure and implement new air traffic control (ATC) tools designed to improve air space management and reduce aircraft operating costs. Modernization includes a new space-based navigation system, new communications with automatic data link between controllers and the aircraft flight deck, and new controller automation equipment in ATC facilities. Also included in the FAA's estimates are support contractors, facility leases, support equipment, and the modernization and/or replacement of many of the 591 ATC facilities.

Many of the new ATC tools, which provide cost savings to airway system users, are now in prototype form. These software intensive systems will help maximize the capacity of congested airspace and airports, reduce delays, and increase direct routing of aircraft. As the FAA's controllers begin to rely on these tools and aircraft separation is reduced, it becomes extremely important that these systems are highly accurate and reliable. These tools represent the building blocks for future "Free Flight" which will allow aircraft to fly the most efficient routes of their choice. Full-scale-development of these systems and implementation across numerous sites with unique requirements is both time consuming and costly.

The FAA's revised requirement estimate also includes an additional $600 million for aviation security based on Gore Commission recommendations. It is an initial estimate inserted for explosives detection equipment at airports, similar to equipment acquired in the FY 1997 supplemental appropriation which included sophisticated baggage checking equipment for installation at the FAA's top 30 airports.

One area in the "navigation and landing" category of the Facilities and Equipment budget has caused concern for members of the Commission. In a recent version of FAA's "NAS Architecture" plan, the agency suggested that certain navigation and landing aids should be the financial responsibility of non-federal parties such as airport authorities. The Commission believes that the FAA has the responsibility to provide a nationwide system of air traffic control services and equipment and that proposals to shift a subset of these responsibilities are inappropriate and could negatively impact on aviation safety.

If F&E investments are not increased, the FAA will have to make tradeoffs between providing improved services and sustaining current services. Reductions in funding to sustain current services will impact the availability and predictability of the air traffic control (ATC) services, due to more frequent and longer lasting equipment failures associated with aging equipment. Because safety will always be paramount, ground delay programs may be used to ensure that NAS safety is not jeopardized. The users of the ATC system would experience increased system delays, mostly on the ground, due to equipment outages and more airports and sectors reaching critical capacity. The users also would experience decreased system flexibility due to the system being operated near its capacity limit for longer periods of time. In essence, without these increased investments, the air traffic control system will approach gridlock shortly after the turn of the century.

Although the RE&D budget is a relatively small portion (about 2%) of the total FAA budget, RE&D is viewed as having a central role in helping the FAA accomplish its missions. The FAA's RE&D budget normally is not used for full scale development of air traffic control systems which is funded under the F&E account. RE&D includes programs in the following areas: air traffic management (ATM) (including Flight 2000 and Free Flight), digital air-ground communications, weather research, surveillance (runway incursions), airway facilities maintenance technology, airport technology (pavement research), aircraft safety, human factors and aviation medicine, and environment and energy.

The FAA's Requirements Estimate recommended more than doubling the RE&D funding to a level of $420 million in FY 2002 from $208 million in FY 1997. This level of requirements was based on an intensive 30 day zero-base review accomplished jointly with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) , and that review resulted in a program report in November 1996. The program report shows funding, levels year-by-year of between $400 million to $450 million, peaking in FY 1999. Examples of RE&D efforts that would be increased under the requirements estimate include:

The Flight 2000 initiatives have not yet been factored into this requirements base. Nonetheless, the requirements estimated (sic) noted above is considered a satisfactory level of funding, assuming cooperative leveraging of NASA, DoD and industry research (NASA currently is proposing to spend approximately $500 million over the next five years on aviation safety research). The Commission supports NASA's role to develop breakthrough safety technologies while the FAA works to improve safety today.

At the current RE&D funding level (approximately $200 million annually), the FAA would be unable to expand its RE&D efforts, especially in emerging areas such as human factors, considered key to improving aviation safety and reducing accidents. Moreover, since some RE&D is intended in part to "create" commercial products/nondevelopmental items (COTS/NDI) that FAA could then acquire cheaply and quickly, the net effect of not making investments would be to increase the cost and time required to acquire new systems through the F&E process. Such a result would unravel the gains of FAA acquisition reform and defer the ultimate cost savings that would be otherwise available through greater productivity in FAA/NAS operations. Finally, there would be a harmful effect on ATM equipment exports, a surplus area for U.S. trade, since these same products are proven first in the FAA environment and then become the commercial leaders in markets overseas

The Commission supports increased RE&D funding but recommends phasing, in an increase over a four-year period. The Commission is skeptical that increasing RE&D funding from $200 million to more than $400 million over a one-year period would be effective. However, if there are new programs, like Flight 2000, which could be implemented independently, specific increases may be justifiable.

The Commission believes that opportunities for cost savings exist within the FAA requirements baseline. These savings may be needed to fund additional capital investments requirements, such as improved radios, not currently included in the budget. To achieve savings, the FAA needs the mandate to operate like a business and provide services in the most efficient and cost-effective manner. The Commission's proposed Performance Based Organization for ATC would help establish a business-like framework for implementing cost saving initiatives. Below are the Commissions cost saving recommendations to be accomplished across the FAA, both within and outside of the PBO for the Air Traffic System. The Commission would expect the PBO to continually look for cost saving opportunities and productivity increases.

Organizational and geographic consolidation of major FAA functions and facilities is one area where the FAA's cost of service can be reduced. Such consolidations can create economies of scale for the FAA, thereby reducing costs, with little or no decrease in quality, timeliness, or other measures of service effectiveness and delivery, and with no decrease in customer satisfaction. In the FAA, regional office consolidation has been discussed repeatedly, but changes have not been made. FAA efforts at facility consolidation have not been successful, and its successes have been needlessly delayed based on political resistance to closing facilities. Clearly the FAA needs to reverse this process and close/consolidate facilities as needed over time for efficiency and cost savings. The Commission recommends that a regional office consolidation take place reducing from nine to three regions. Studies have shown this consolidation could reduce the FAA's operating costs by nearly $100 million per year while improving or standardizing services.

Additionally, the following specific actions should be considered:

The savings considerations above could cause significant discomfort within both the FAA and the Congress. The FAA's new Performance Based Organization (PBO) for the Air Traffic System will provide the organizational structure to support these cost saving recommendations. A PBO coupled with the proper budget treatment which allows the FAA financial flexibility, will lead to an improved aviation system for all customers and stakeholders.

| Return to Avoiding Aviation Gridlock: A Consensus for Change Index |